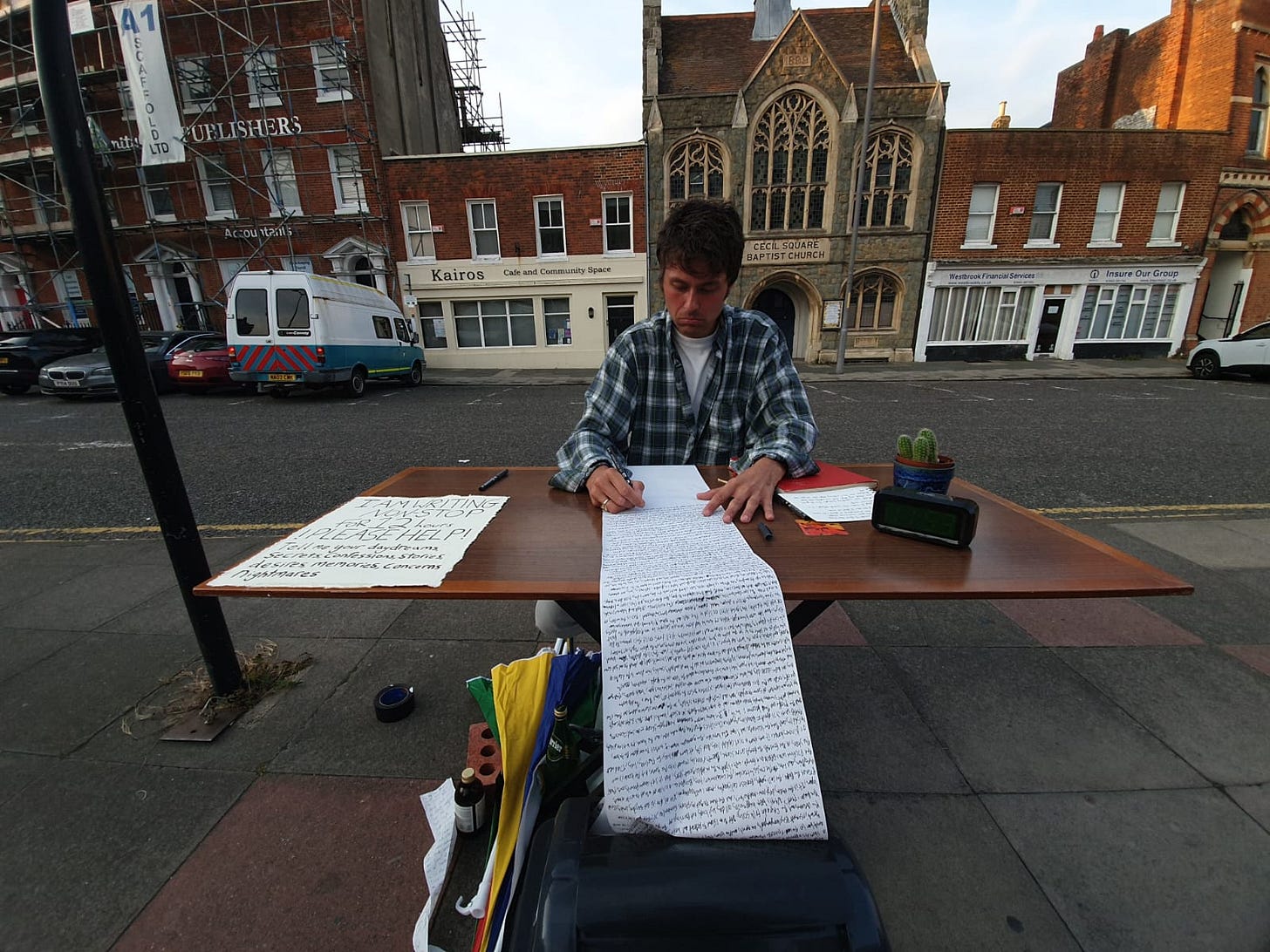

On the 21st of September 2024 I wrote non-stop for twelve hours. I set up a desk in Cecil Square, Margate, between two bus stops. On my desk I had a sign that read:

I am writing non-stop for twelve hours ! PLEASE HELP ! Tell me your dreams, secrets, confessions, stories, desires, memories, concerns, nightmares.

I started at 6am. By 6pm I had written, by hand, 7.8 metres of scribble on a 30 metre roll of fax paper. I did not stop to urinate, when nature called I took a notebook with me to the bathroom and carried on there.

Cecil Square is no one’s fault. Don’t blame poor Cecil. 1769 the cornerstone reads, the year Mr Cecil laid it. A Georgian square – first of its kind, it was. Hear the horse feet clopping on the tamped mud now glazed with hot tarmac. Over there, a Royal Hotel and Assembly Rooms. Hear the flames roar as it burns to the ground. Hear blokes on the way to get their haircut and their boils lanced. Hear, quite distinctly, how unbalanced their humors are. It’s a square from a simpler time when squares were squares, just like nana used to make.

Cecil Square Margate, England. Sometime in the 19th century.

I say Cecil Square is no one’s fault because really it’s everyone’s fault. A place of pure necessity. Built to regulation. No one argued against the convenience of it all. Everyone agreed it must be up to code. A square from The Age of Reason, a product of Rationality, with its bilious right angles squared by round Saturn Heads.

Little by little, the council optimised the space. Now it resembles nothing more than a sorting facility at a cattle ranch, milked dry of inspiration.

Cecil Square, Margate, England. Present Day.

To be there is to be fed on a trough of empty calories – flashing lights, honking cars, a ticket inspector tucking a fine under my windscreen wiper.

However, underneath the square, down in the chalk there’s a cave and an Argentinian woman dangling from her carabiners. She tells me this. How she’s stuck in indecision of whether or not to let go, of whether or not to plunge into the sleeping black pool of water.

She’s in front of her mates. She’s got Latina guts and tells us how she’s down there right now, confidence greater than spelunking self-consciousness. I write and write her dream. It was not a dream she had had. She was having it there and then with her mates listening – and I – a stenographer working – recording the events of the day.

She was only one of the people who stopped to tell me their dreams. Their memories. Their nightmares. ‘Nightmares? You want to hear about nightmares? I’ve snorted so much fucking cocaine I ain’t slept, I’m in the fucking nightmare.’ This man: blue-eyed, blue-collared, around three pm on a Saturday. He leaves with a shake of my hand, calloused skin thick as a butcher’s block. I could scrape it away like parchment to write my revelations. I write, ‘Hell does exist.’ I write, ‘Hell is bad decisions.’ And with some semantic algebra I can report Heaven is Good Decisions and this should bring us all peace.

I imagine CCTV footage of the square. The screen, an illusion itself, an assemblage of red, green and blue. Pixels mixed to create the colour image of cars and buses and pedestrians and pigeons and seagulls and ‘everything’ that’s ‘happening’.

But there’s more going on. There’s a mother and child waiting for a pterodactyl to come and pick them up. Or maybe an eagle, since the restless little girl doesn’t know what a pterodactyl is. This thought offered by the mother keeps the little girl entertained. The mother, she got it. That was exactly the reason why I was there.

My idea was that bus stops are places in which we wait to go somewhere, physically, in location. Yet, as we wait, we go somewhere else, not in location. We wait and we ponder. We day dream.

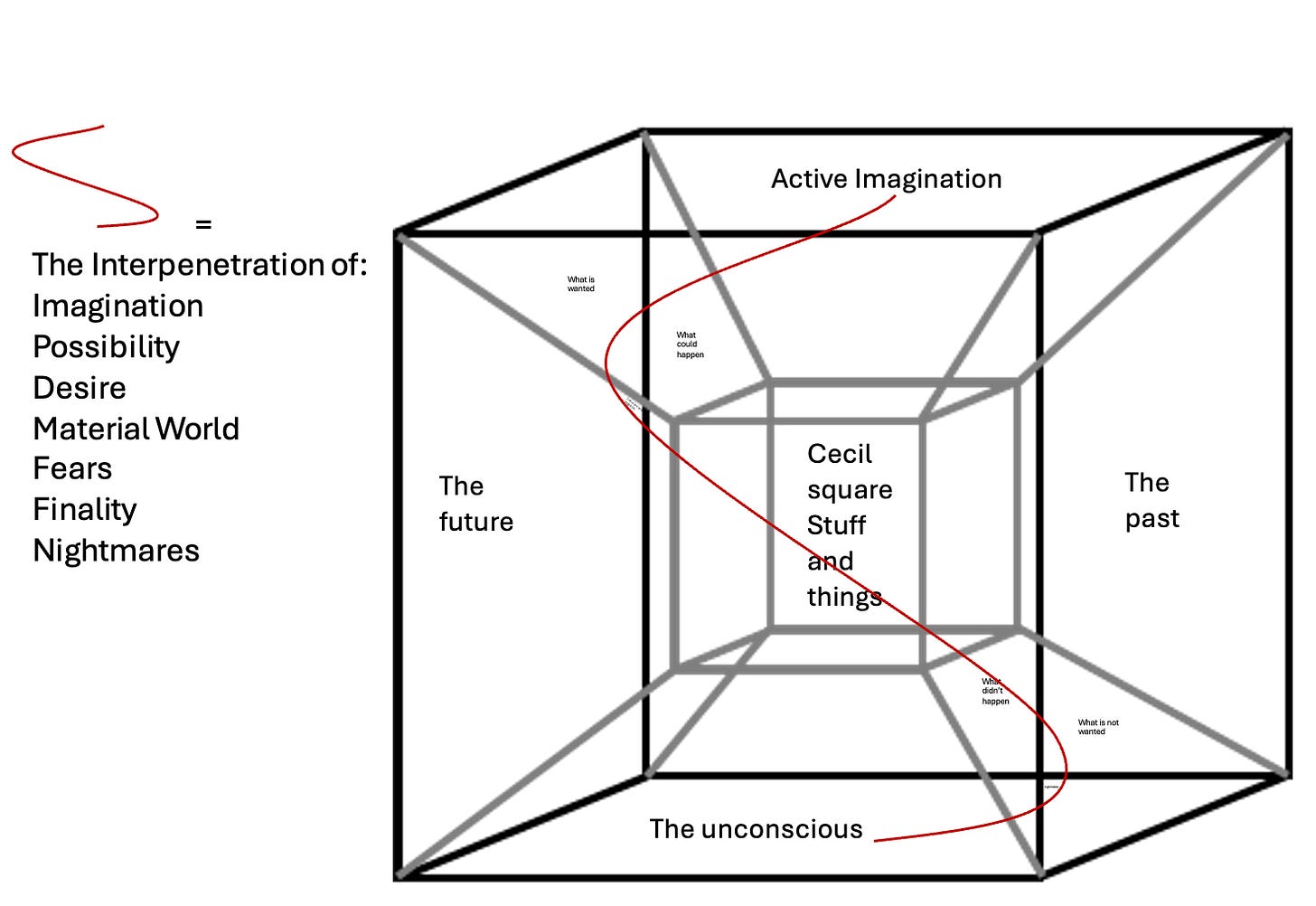

Bus stops as pockets of stillness are mental launch pads. What we with our CCTV eyes see as drab pavement and plastic shelters is in fact a theatre of imagination. A multi-dimensional space where dreams and histories are just as real as seagulls and buses. Alive with hidden layers, the bus stops in Cecil square I thought were nodes in the cosmic web of everything.

Although, a dense fog of the mundane still blinded most. You can’t blame them. The effect of the environment is overpowering. The red brick buildings with concrete windows making up the library and the courthouse bulge into the sky like a tumorous growth. Traffic lights, four sets; a median covered in weeds and littered with cans of Monster Energy. An advert for McDonald’s Monopoly – that conjunction of the profane the most colourful thing you’ll see. And the tarmac and the car park, all grey and faded council paint. There are no trees. They’ve taken most of the bins away because people keep burning them so now, in place of leaves, litter flutters, pecked at by petroleum-blooded seagulls dying for a fix.

But what if that CCTV could see imagination? Then Cecil Square, with its four bus stops, it’s network of energy-efficient LED streetlights, mounted on 5-meter-high poles, spaced uniformly at 15 meters; with it’s reinforced concrete slabs designed to accommodate both pedestrian and vehicular loads; with it’s accessibly compliant pathways per the Equality Act 2010; Cecil Square would, in fact look like a firework display of exploding moments and bursting forms – the splintered past, present and future co-existing, there, at universal Longitude 93.2 – Latitude -0.06, in the spiral arm of the Milky Way, on the planet called Earth.

You’d see a woman who is actually a louse living atop her own head. It’s her job, as the louse, to number and organise all the strands of hair. This causes her great anxiety. You’d see a little girl with her father in a tomato patch – he warns her of snakes and when she reaches for the tomatoes they become eggs, cracked open snake eggs and now the baby snakes are in her hands and she’s not so afraid anymore. They’re just babies, like her.

The typical plane of perception – the one on that screen capturing all things, the one in our eyes that sees only stuff – does not exist independently, nor is it primary. Viewed as a tesseract, a four-dimensional Cecil square, the dimension of ‘things’ and ‘stuff’ occupies a surprisingly low place in the hierarchy of ‘What Is Happening.’

That teenager there, skulking home – pigeon-footed, gap-toothed, acne-cracked – he’s not here in Cecil square. He’s in the midst of an existential crisis. He’s in the depths of a war. He’s actually still at school, trapped in the moment he got slapped in the stairwell. People are still laughing at him.

His body may be here, trudging past the drunk woman Snapchatting her daughter, but he’s still in that stairwell. The laughing hasn’t stopped.

And I always wondered how it is old fellas can sit for hours on a bench looking at nothing. I now know they’re not looking at nothing.

They’re re-living their entire lives. They’re un-living what should not have been, in-living what should have been. Could have been.

They’re seeing the Hippodrome go up in smoke. They’re seeing the trees cut and the bollards go up.

‘Used to be a nice place, this. Came here in the 60s. We met at that cinema, didn’t we?’ An old couple stop and point across the street. They gaze longingly at what is now cement steps leading to a shuttered entrance of the magistrates court.

This is why I wrote non-stop for 12 hours. To tear the fabric of things and stuff. In becoming a relentless witness, I was granted passage into the worlds behind the veil of the Ordinary. I’d set-up, not a bus stop, but a ‘dream stop’ where my desk was not just a physical object but a threshold to anywhere.

And although my arse was firmly planted on the seat, I was taken in hand through a Tudor house with no exit, each room opening up into another room, ornate empty room after room, until this woman and her brother open a window and we’re outside and there’s a mist in twilight and it’s all so beautiful, the garden in the mist; and then the woman and her brother take me over the fence into the next garden and the next, and each one is more beautiful than the last.

The woman’s eyes glazed over. She was embarrassed. She said, ‘I guess that’s just nonsense, really.’ But she couldn’t have been more wrong.

A crowd formed. ‘What’s this then? Oh god, he’s not recruiting for the Socialist Worker, is he?’

‘I just want to say: Peace and Love.’

’End All Wars.’

‘Love everyone.’

Those were the most frequent things said to me, by those passing by. I wondered why? And then I thought about the future and the people who live there reading this. Maybe they’ll see we weren’t so bad after all.

This lady stops, reads my sign. ‘Jesus Loves you,’ she says. She’s Russian. ‘Write that down.’ So I do. ‘Don’t be mean to people,’ she carries on, as if I’m chiselling some new commandments. ‘It make Jesus sad. Why, why do people make Jesus sad? He want us to love everyone and have peace, Jesus, I love Jesus, Jesus love you,’ she says. Jesus love you, I scribble. She smiles. She says. ‘Dostoevsky, a writer from my country, say you can tell man’s character by’s smile. And you have LOVELY smile. I LOVE YOU! BEAUTIFUL!’ She pinches my cheek. Ignoring the smell of vodka, I write ‘ouch’.

Me. The timer reads 11:59.

When I saw the numbers 11:59 on the timer in front of me (eleven hours, thirty minutes) my blood thickened. Every flick of the wrist felt like the last laboured steps before reaching the peak of Everest. Time slowed. Time was a living thing responding to my pokes and prods like a snail’s eye recoiling and emerging.

Time was malleable. The ebb and flow of the day is present in the scroll. The writing small and squashed in the dragging times, when time laboured against me and drew out all doubts. ‘I’m wondering why it is I am doing this and yes what the fuck, im stuck here, now, now, im stuck here and I cant get up can I what a dickhead id be if I stood up right now and gave up.’

And then there’s the larger letters, the ones that grow with the sentence, that puff their chests, breathe deep and shout – ‘I write about the you I say you, you when I’m I , an I in me, there’s me in the you and me in the I – it’s not only one voice in Me, there’s Me You And I, so when I hear you I need to know which part which part, is calling me by my name.’

The clock tower struck six, bells tolling the twelve hours. The portal now closed. The veil fell back over my eyes. My hand crippled into a claw. The scroll lay at my feet, a crinkled mass of spilt ink dreams. I was in Cecil Square. Seagulls gulled. Cars honked. Bus brakes hissed…